A new scientific study paints a grim picture of how our planet may meet its end — and when it could happen.

Scientists now believe that Earth’s ultimate fate may already be sealed — and they’ve even proposed an approximate timeframe for when our planet could meet its fiery end.

The alarming theory comes from a recent study published in the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. Researchers from the University of Warwick and University College London worked together to explore how the end of the Sun’s life cycle could spell disaster for the planets orbiting it, including Earth.

The paper, titled “Determining the impact of post-main-sequence stellar evolution on the transiting giant planet population”, outlines what might happen once the Sun exhausts the last of its hydrogen fuel — a process that will occur far in the future but carries immense consequences for our solar system.

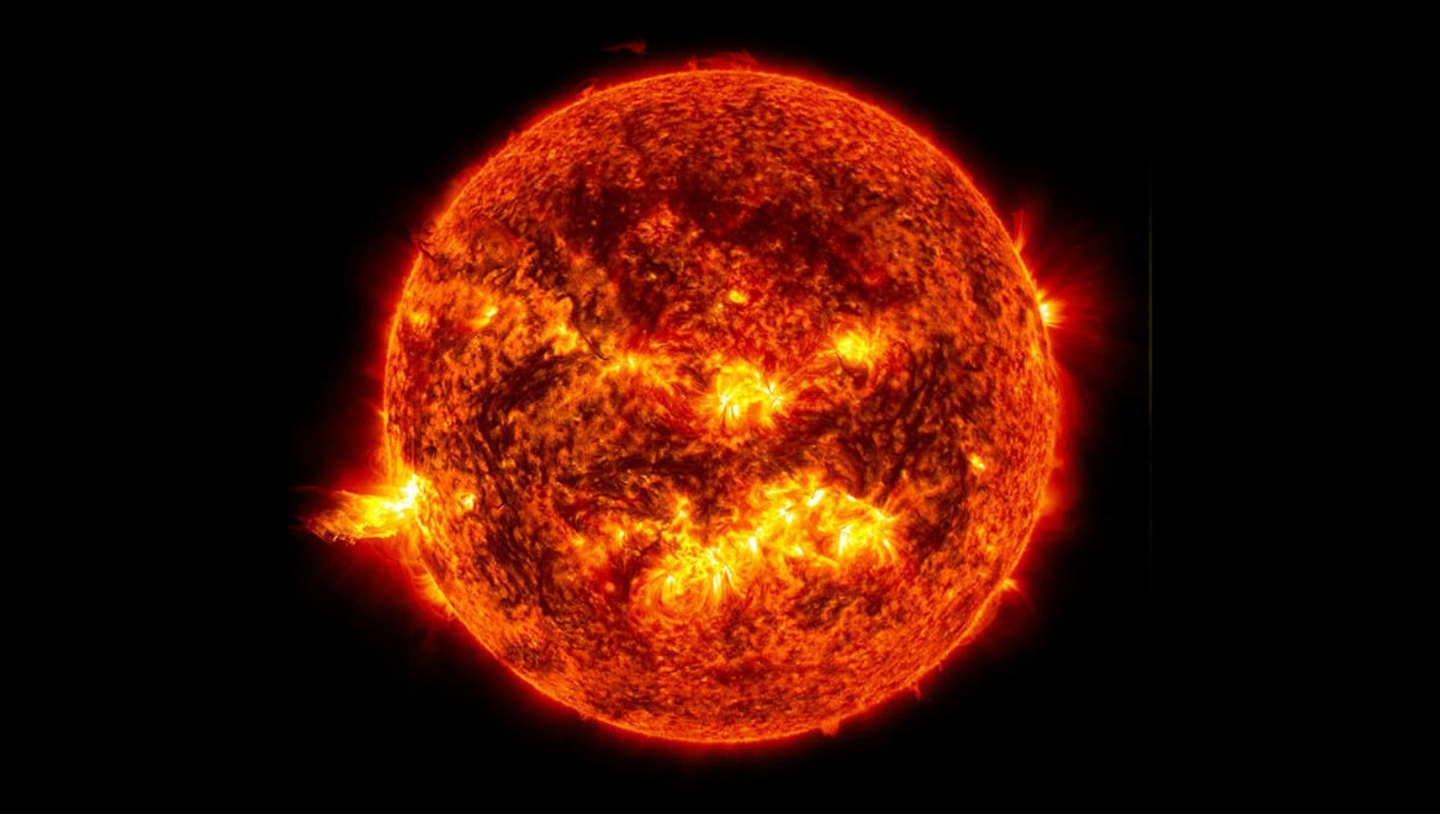

When that stage arrives, the Sun will begin to transform into what astronomers call a red giant — a dying star that expands and changes dramatically as it reaches the final stages of its evolution, according to Space.

As this process unfolds, the swollen Sun will likely engulf Earth or rip it apart completely, scientists say. Either way, the planet as we know it would not survive.

Based on current models and stellar data, the researchers estimate that this catastrophic event could occur roughly five billion years from now — an unimaginably long time away, yet inevitable on a cosmic scale.

Discussing the findings, lead researcher Dr. Edward Bryant, an Astrophysics Prize Fellow at the University of Warwick, explained that Earth will eventually be drawn inward toward the Sun due to the powerful influence of something called tidal forces.

These tidal forces are created by gravitational interactions between celestial bodies, as described by the National Ocean Service (NOAA). They play a major role in determining how planets and stars affect each other’s motion.

"As the star evolves and expands, this interaction becomes stronger," Dr. Bryant said, noting that the pull between the expanding Sun and nearby planets grows more intense as the star evolves.

"These interactions slow the planet down and cause its orbit to shrink, making it spiral inwards until it either breaks apart or falls into the star."

To reach these conclusions, the research team analyzed data gathered by NASA’s Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite, better known as TESS. This powerful space telescope scans the skies for changes in brightness that could indicate a planet passing in front of its host star.

According to the Royal Astronomical Society, the scientists used computer algorithms to sift through the TESS data, identifying tiny dips in starlight that revealed the presence of orbiting planets — or, in some cases, their destruction.

Out of approximately 15,000 potential planetary signals, Dr. Bryant and co-author Dr. Vincent Van Eylen, an astronomer and Associate Professor in Exoplanets at the Mullard Space Science Laboratory at University College London, confirmed 130 planets and planet candidates.

Among these, 33 were entirely new discoveries. The newly identified planets all orbited extremely close to their stars — a pattern that caught the researchers’ attention.

After analyzing the data, the team found that stars that had already expanded and cooled into red giants hosted fewer close-orbiting planets, suggesting that many of those planets might have already been pulled in and destroyed as their stars evolved.

"This is strong evidence that as stars evolve off their main sequence ,they can quickly cause planets to spiral into them and be destroyed," said Dr. Bryant while discussing the results of their work.

"This has been the subject of debate and theory for some time but now we can see the impact of this directly and measure it at the level of a large population of stars."

"We expected to see this effect but we were still surprised by just how efficient these stars seem to be at engulfing their close planets."

Dr. Van Eylen, however, offered a slightly more hopeful perspective, saying that while many of the planets they studied were likely consumed by their stars, Earth could still have a chance of surviving the Sun’s red giant phase — though in a much-altered solar system.

"But life on Earth probably would not," he added, noting that the unique position of our planet could give it a slim margin of survival even as the Sun expands.

With the data now in hand, the researchers plan to continue refining their estimates of the planets’ radii and compositions. They also aim to determine whether some of the identified objects are small planets or failed stars that never fully formed.

According to the Royal Astronomical Society, one way to confirm these findings is by measuring the tiny “wobbles” of host stars — subtle shifts in movement caused by the gravitational pull of their orbiting planets. These measurements can reveal a planet’s true mass and help scientists understand its fate.

Dr. Bryant concluded: "Once we have these planets' masses, that will help us understand exactly what is causing these planets to spiral in and be destroyed."